I’m not really sure where to begin with this one. I had always assumed that warfare was all about troop movements, logistics, and diplomacy. I don’t know how I could have been so wrong. No, as Sting’s Knights in the Nightmare has shown me, success on the battlefield is purely determined by magical ghosts, fractal bullet patterns, and slot machines. Unfortunately, the game’s educational potential often gets buried beneath its cluttered interface and bewildering surplus of mechanics.

Your “character” in Knights in the Nightmare is the stylus-controlled Wisp, the ghost of a murdered king who now commands an army of his murdered soldiers on a quest to murder his murderers. The story (loosely connected to Riviera and Yggdra Union) is told through cutscenes between battles, and employs such traditional Japanese storytelling techniques as flashbacks within flashbacks and the heavy use of vague pronouns rather than characters’ names. The world of Aventheim apparently suffers from a severe case of chronic fog, but the 2D graphics beneath the murk are colorful and atmospheric, drawing on the popular “Epic Precious Moments” school of character design. The soundtrack is pleasantly fast-paced and is included on CD so that you can enjoy the grainy DS audio anywhere, anytime. The awkwardly acted voice clips, on the other hand, will annoy the hell out of you after about, oh, the first time you hear them.

Now comes the part where I talk about Knights in the Nightmare‘s gameplay, a.k.a. the part where the review starts to sound like some sort of cult initiation.

The central gameplay concept is an interesting fusion of turn-based SRPG and real-time shmup: you place a variety of unit types on an isometric grid-based map, and then hover over these units with the stylus to make them attack. While dragging the Wisp between units, you must weave your way between the complex streams of projectiles unleashed by roving monsters—every time the Wisp takes a hit, you lose a bit off the timer for the turn, which therefore reduces the number of attacks you can make that round. Hitting monsters with basic attacks does little damage but releases gems that can be collected with a swish of the stylus to gain MP. MP is then spent on powerful damaging attacks that are activated by dragging weapons from the sidebar to your units. To add a bit of strategic thinking, the various unit types have limitations on which weapons they can use, which directions they can face, and how (or if) they can move while attacking. Also, you can switch between Law and Chaos phases at any time, which changes the pattern and range of attacks and which weapons can be used. Got all that? No? OK.

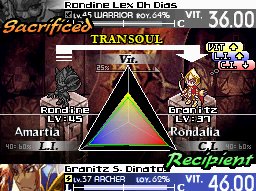

If this was the whole game, it would be a solid, fun, unique experience once you got over the learning curve. Alas, the developers didn’t know when to stop, and proceeded to insert every single gameplay mechanic they could think of. It’s not enough to just consider unit type and placement: the game also wants you to consider elemental affinity, weapon durability, unit vitality, hit counter, regen damage, rush effects, obstacle fragility, key items, kill reels, barometric pressure, and the doctrine of papal infallibility, all in real-time. Nearly every pixel of the screen is occupied by icons, meters, and counters, but these tend to confound the situation more than they clarify it. Between battles, you get to experience the joys of inventory management and make use of the esoteric “Transoul” system to merge your accumulated units, thereby boosting their stats and level cap. The exact equations that govern this procedure are not particularly clear, and it’s recommended that you carefully examine the entrails of sacrificed livestock before you attempt anything. The result of this whirling chaos of gameplay mechanics is a constant sense of confusion: Am I playing the game right? Did I merge the right units in the right order? Why does this feel like homework? The game throws so much at you at once that you never really get a clear sense of progress or a feel for the relative strength of units and weapons. The first few times I saw the “VICTORY” screen, my reaction was not “I won!” but rather “I… won? Probably?”

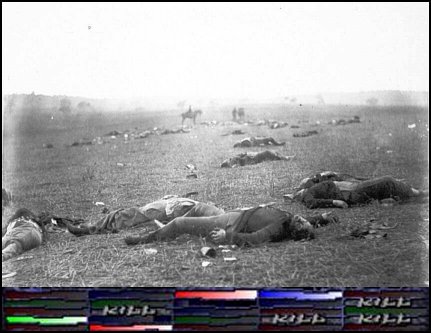

Two mechanics in particular interact in such a way that they drag down the overall experience. Battles are not won by simply killing all enemies. Instead, kills are marked down on a matrix, and on the next turn new monsters will spawn based on the results of spinning slot-machine reels; the battle is thus won by lining up a complete row of kills. This mechanic by itself, though odd, really isn’t that bad: it provides the clear goal of lining up kills on the matrix as quickly as possible. However, new characters can only be recruited by giving them key items, and these key items must be obtained by attacking stationary obstacles on the map. Worse still, objects sometimes contain two key items or a powerful weapon, and must be destroyed and then allowed to respawn after a few turns so that you can collect the second item. The curious result is that you’ll spend much of the game avoiding lining up kills so that you can drag battles out and farm items.

I’d like to dock the game for all this gameplay-flow obstructing nonsense, but I know that there are gamers out there who really eat up this “gotta catch’em all” stuff. For the rest of us, thankfully, there is a solution: dismiss all of the units from your army. Most SRPG fans are probably convulsing on the floor at the very suggestion, but clearing out your army will cause the game to provide you with “nameless knights” for each battle, who come with their own infinite durability weapons. No more worrying about the Transoul system, no more farming for key items, no more wasting turns to manipulate the mechanics rather than actually playing the game. The difficulty isn’t really balanced with these low-stat nameless knights in mind, but for many players this has nevertheless proven to be a much more enjoyable approach to the game.

I’d probably rate Knights in the Nightmare a 5 purely due to its divisiveness: some people will love it, others will hate it. It often borders dangerously close to being more of a gnostic numerological meditative exercise than an actual game, but it gets a bonus point for the originality of the core concept, which can be enjoyed if you take the counter-intuitive step of dumping all your characters. All I can suggest is that you give it a go if your interest has been piqued, but don’t blame me if the raw originality proves to be more than you can withstand.

I would have to agree with this review. This is not a game for the average gamer. While I really enjoyed this game I can completely understand why someone could dislike it. I would have to say that playing it on normal difficulty is almost too easy because you can just keep trying multiple times after you have lost with the only penalty being your score. You can even abuse you knights and kill them all because they always make sure you have one of each one as a guest complete with weapons; granted, they royally suck but can still get the job done.

Can’t most games that are excessively complicated be deemed pretentious, due to the target audience for most video games being teenagers? I don’t understand why some developers make games that, as you pointed out, only appeal to an esoteric group.

i had been wanting to get this game for a while now…and i believe that my attitude on the subject has changed.