Sometimes, when you’re a guy who reviews games, you gotta play a game whose genre is outside of your range of expertise. This is partially where I find myself when it comes to The Wild Eternal. This independently published title is a game that’s defined by an experience to be had, rather than the thrill of accomplishing it. This is not to preemptively diminish my critique of the game, but I feel it’s prudent for me to share where I’m coming from before we get started here.

The Wild Eternal starts out promisingly by immediately highlighting mechanics that separate it from the”walking simulators” that are often associated with narrative-driven games. For those who aren’t familiar with this particular terminology that I have arbitrarily placed into my vocabulary, “walking simulator” is usually a derogatory term used to describe a game with such a strong narrative focus that the gameplay ends up being reduced to you controlling the character walking from plot point to plot point. In my opinion, there are certainly select cases where this style works wonderfully, but in the indie game scene it’s often simply a way for someone to tell a story they want to tell without having to worry about pesky things like “game mechanics”. The Wild Eternal seems to contain that same framework, but more effort has been given to make moving between the narrative elements some sort of gameplay experience.

At the beginning of the game, you are very quickly introduced to mushrooms that bounce you high into the air, as well as various powers you can obtain by collecting “tributes” hidden around the landscape of the levels. These features, while simple, provide great opportunity for you to tune your gameplay experience to your liking. For example, you are first given the option to choose whether to gain the ability to run for a short period of time or be able to slide down slopes without taking damage, which will decide whether you overcome your first dead end by jumping over a broken bridge or by sliding down the cliff-side. Had options like these continued to make themselves prevalent throughout the course of the game, the mechanic could have sold me on exploring the world to find challenges to overcome with newly attained powers. But alas, as I slid down the mountain into the Himalayan valley below, the main challenge of the game reared its ugly head.

An example of the hidden shrines used to gain abilities

An example of the hidden shrines used to gain abilities

The visuals of The Wild Eternal do fall under what I would call aesthetically pleasing. They are not, however, what I would call varied, at least within each individual level. I constantly found myself completely lost and unaware of where I should go or what I should do next. Of course, perhaps I should pull back and take note that not all games are there to be sped through to reach an objective. The Wild Eternal has marketed itself as a “meditative” and “relaxing” experience, so one might suggest that I simply take my time to wander and reap the calming benefits of the serene forest.

Yet, amidst my wandering I rarely found anywhere interesting or of any particular note that wasn’t somewhere on the critical path of the game. In between the various landmarks containing the Glowing Plot Orbs that allow you to advance through the game, there are a lot of the same ground texture surrounded by the same rock texture with a bunch of the same trees. Most of the game’s principle areas are a few landmarks surrounded with a lot of filler to make the world seem like it has more content than it actually does. So getting lost on your way to a landmark doesn’t really provide you with any experience that you wouldn’t get making a bee-line for the plot or walking around in a few circles before moving on.

Now, to the game’s credit, there is a compass item which not only has a general direction pointer but also the ability to tune pointers to the various checkpoints around the world. This does help with navigation somewhat, but often I was only able to use it by pointing it to a checkpoint and then making sure to walk directly away from it in hopes I would find a useful door on the other side of the map. Without identifiable landscape elements along most of the paths, the extra compass orientation does little to help. The frustration is increased by the fact that the first level presents an interesting solution to this navigation problem by letting you climb to a higher elevation to look out and see where you need to find important landmarks. You can then use your scouting to remember where to walk once you return to the dense forest of the valley. Sadly, this mechanic is not utilized in the levels that follow, as there are no high vantage points with strong visibility (at least that I could find). In the end, I spent a lot of time wandering the same sections of areas simply because I had no sense of whether I was on a path that I had traveled before until I walked all the way to a landmark area I had been to before.

Now let’s take a brief aside to discuss the narrative. You may be wondering why—in a game whose genre so heavily relies on narrative—I did not discuss it earlier. First, if I may be honest, narratives in games like these are still rarely as appealing to me as gameplay. In the end, if you just want to tell a story with text boxes and voice overs, I feel like there are more apt genres or even media that you could use. Visual novels give you all that juicy narrative without making you spend fifteen minutes walking around, and written or video media can really hone in on a story or character if that’s what you want to focus on. Still, barring my personal opinions, I feel that the narrative of The Wild Eternal is very weak, or at the very least is not aided in impact by the structure of the game.

Explains why you’re such a sparkling conversationalist

Explains why you’re such a sparkling conversationalist

The Wild Eternal’s protagonist is an old Himalayan woman named Ananta who has grown weary of the world and wishes to break her path in the circle of reincarnation. The various landscapes you travel are part of this sort of ethereal plane that the god of death has brought Ananta to after hearing the old woman’s request, and you meet a godly wayward spirit in the form of a fox who aids you on your mission to go to all the places so you can grab the glowing things that let you go to the other places. Most of the dialogue in this game is between you and this fox, as you slowly uncover the backstory of Ananta and why she wants to break out of the cycle of reincarnation. The thing is, the places you explore have nothing to do with Ananta or her life as they are part of this spiritual landscape rather than the “real world” that Ananta came from. As such, all of the knowledge you discover about Ananta comes from dialogue, and exploration won’t give you any more information about her character unless it triggers a dialogue section. Better examples of this style of game will make finding things in the environment just as enlightening to the narrative as the text found in the game, whereas here it only vaguely alludes to the backstory of the fox-god, and even that I found unsatisfying. It doesn’t help that the dialogue itself isn’t very engaging. There’s a lot of philosophical waxing that’s to be expected of this type of game, but I was a little put off at times where the game seemed to try to provide direct answers to these topics, and it was hard to tell if Ananta was supposed to be a relatable protagonist to project onto or a character with a story for me to observe more than experience. The voices added over these dialogue sections were also unhelpful especially since I’m mostly sure the word-sounds were completely made up and non-contextual. They rarely, if ever, emoted, leading to weird neutral speaking tones during scenes that were supposed to have angry or emotionally broken characters.

As I progressed through the game, I also found that many of the abilities that you earn were not incredibly empowering. On the contrary, some even seem like the game returning basic functions to you that should come implicitly with this type of game. Not being able to read any of the text scattered throughout the world makes much of the exploration feel awfully fruitless, and the inability to run makes being lost even more frustrating. Perhaps the power-ups become more engaging as you unlock the ability to acquire new tier-sets, but as I have said I didn’t enjoy exploring the worlds enough to find many tributes that would let me add abilities to my character. The only starting disability I sort of liked was your lack of perfect vision before acquiring any power ups (a feature that is suspiciously absent from promotional pictures). You could gain visual clarity by zooming in and reducing your movement speed, which really added to the sense of “ooh what’s that over there” that’s important for this type of game. I would actually call that The Wild Eternal’s greatest strength; it is very good at making things look interesting from a distance.

Despite all I’ve mentioned above, what really solidified my sour tone with this game was its lack of content and abrupt ending. It is not uncommon for indie titles like this to be on the shorter side and have only a few hours of core gameplay, but—without spoiling anything—the ending isn’t really an ending but more of a transition in the narrative after which there is no additional content. The final area of the game features several doors to areas that are inaccessible, and if my research of the developer’s comments are correct, they do not actually exist within the game. It has been mentioned that there might be more content added depending on the game’s success, but given this was a full release rather than a beta or something, the situation has left me somewhat uncomfortable.

During one of my early wanderings in The Wild Eternal, I really tried to buy in to the meditative experience I thought the game was trying to foster. Almost immediately after starting to relax, I ran into a tiger that attacked my character. Maybe that sums up some of the biggest issues with the game. Getting lost in a world can be nice and having to avoid natural hazards can be fun. However, if a game’s mechanics aren’t all working together to build each other up, in the best case scenario each one will have to try to be good on it’s own individual merits, and in the worst case they will conflict with each other to make all of them more annoying. I would only recommend The Wild Eternal to someone who really enjoys the genre and seeing how indie games try to bring ideas together. As for everyone else, if you want to meditate I suggest doing it the old-fashioned way, particularly in the absence of deadly predators.

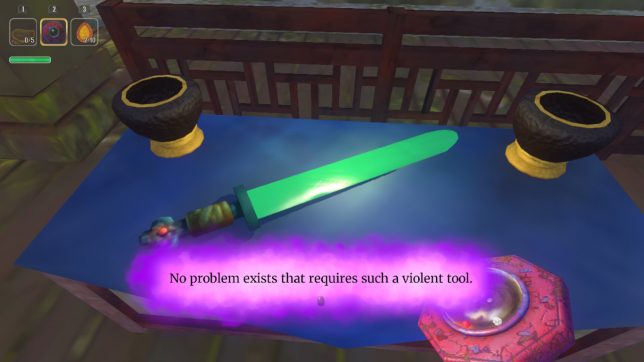

Ma’am, we have been attacked by several jungle creatures.

Ma’am, we have been attacked by several jungle creatures.

[Editor’s Note: A review copy of this game was provided by the publisher.]