Uh, warning? If you care about Call of Duty at all, and for some reason you haven’t played Call of Duty Black Ops II, there will be slight spoilers for this (and a few other) games in the following paragraphs.

Uh, warning? If you care about Call of Duty at all, and for some reason you haven’t played Call of Duty Black Ops II, there will be slight spoilers for this (and a few other) games in the following paragraphs.

There I was, at the end of the mission Achilles’ Veil in Call of Duty: Black Ops II, taking control of Farid (a spy ordered to serve as a mole inside the populist movement of Cordis Die) as Menendez (the game’s main villain) ordered me to show my loyalty to him and kill Harper (an American ally captured by Menendez).

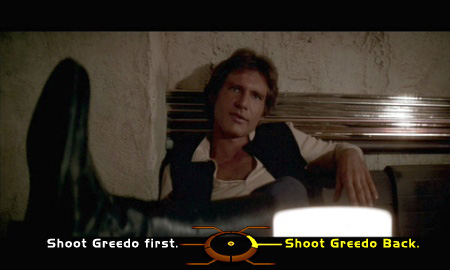

The game gives me the option of either carry on the command, or to disobey and shoot Menendez who is standing right behind Harper. I decided to kill Harper. But not only had I done it because I knew I was being fooled (the whole mission reeks like a setup), but mostly because that moment doesn’t seem like the time to kill the game’s main villain. So I pulled the trigger, Harper died, and then a gun-blazing ally gunship came to the rescue, making me think “oh, no…if I waited just a second or two…”

But then I wasn’t really surprised when I learned that, if you try to kill Menendez, the attempt will end up in failure; Menendez will Kung-Fu your arm away before you can pull the trigger, and shoots you back; if this happens, the gunship takes its bloody time to make its appearance, and Menendez even has enough time to monologue before putting an end to your misery.

From the developer’s perspective, that was a crucial choice I had to make that will have an impact on my game’s progress—for me, “They’re just making stuff up as they go along.” I didn’t feel part of the story, I just felt dragged along to any of the two outcomes they had already prepared.

Of course there are good and bad examples of decisions or “moral choices” in gaming. But I have to say that these have lost much of their magic on me now that I’ve seen how developers have just used them to create shock value, or a sense of “depth” to their stories.

Of course it’s not the first time I’d been placed in a situation like this. Another very notable time happens in Splinter Cell: Double Agent. Normally, I’d warn you about the following spoiler, but the scene I’m going to talk about is right there, in its official trailer (but still, you can skip the next three paragraphs if you want to).

During the final mission of the game, you’re ordered to kill Irving Lambert (Director of Third Echelon, a main character of the series, and close friend to the game’s protagonist Sam Fisher), and you have the choice to do so, or to kill Jamie Washington who is ordered to kill you if you don’t carry out the command.

This was actually a really cool scenario, since the rest of the game will play differently depending on your choice: if you decide to kill Lambert, you won’t be blowing your cover and will have an easier time completing the rest of the mission; if you decide to spare Lambert and shoot Washington instead, you can still carry on with your mission, but the task will be a lot harder since everyone will be after you.

The outcome of this decision doesn’t end right there, since saving Lambert is the only way you’ll get an extra final mission where you have to defuse a bomb being transported to New York’s bay area. All of this was great at the time, except that your choice doesn’t matter at all, since Ubisoft decided to keep the death of Lambert by the hand of Sam Fisher as canon for their next release of the series Splinter Cell: Conviction.

So, what’s the point of all of this? Seriously, don’t give me a damn gun if you’re not going to follow through.

And of course, any discussion about in-game decisions can’t be completed without mentioning the ending controversy in Mass Effect 3. I won’t spoil anything ahead; I’m just going to mention that the final outcome of the trilogy was ridiculed over and over: from a certain comic being overly optimistic about how much your decisions would turn the fate of the galaxy around; how much the fans hated the lack choice in its endings; how that led many of them to protest by donating money to Child’s Play only to be shot down later on; then some others got creative and geared up to send three-colored one-flavored cupcakes to Bioware as a protest; and that finally led Bioware to finally release an extended cut of the ending of the game for free.

You want to get the good ending, don’t you?

You want to get the good ending, don’t you?

Of course videogames, as an interactive medium, can do amazing things with the addition of choices and different endings, but in order to do so, these need to be built with these choices in mind from the ground up, and—more importantly—commit to how these choices will affect the story you’re playing.

Going back to that aforementioned Call of Duty moment that broke the illusion of choices in videogames for me, if an aircraft will come one second or one minute late depending on a choice that doesn’t have anything to do with it, that’s complete garbage. I know they wanted to make things more dramatic, but if they want to tell a story, I’d rather if they just told that story already, instead of making the player an unwilling accomplice of something we don’t have any control over.

Everything that happens in a videogame is an illusion all right—moral choices and similar storytelling tricks are not as deep as they seem. They’re nothing more than a set of conditions that will either trigger a cutscene or another, or hide “that good ending” from you or not, but games that can pull you into that illusion are those that takes these choices and their storytelling branches as a core part of their design. Any Telltale Games title knows this because it doesn’t drag you along; it let you believe that those decisions you make are your own, and they have an impact on what might happen later.

For bad actors like Call of Duty up there, I think there’s no shame in just browsing for the alternate endings or cutscenes on YouTube—and quite specifically for Black Ops II, those alternate endings are not really great to begin with.

Maybe beside the point, but…what the hell is this?!