![]() Ah, King’s Quest. Arguably Sierra’s most famous and popular series of adventure games, King’s Quest introduced a generation of gamers to the wonders of endless backtracking, puzzles built on moon logic, arbitrary choices that make the game unwinnable, text parsers that don’t recognize essential commands like ATTACK PORRIDGE, and incomprehensible graphical representations of whatever that thing in the corner is. After five installments, you might expect to see some stagnation, but King’s Quest V is unlike anything previously seen in the series: you’ll visit a vast ocean and a dangerous castle; you’ll make friends by playing musical instruments; you’ll confront bandits, face off against a deadly snake, outwit a yeti, and OK it’s exactly the same as all the other games.

Ah, King’s Quest. Arguably Sierra’s most famous and popular series of adventure games, King’s Quest introduced a generation of gamers to the wonders of endless backtracking, puzzles built on moon logic, arbitrary choices that make the game unwinnable, text parsers that don’t recognize essential commands like ATTACK PORRIDGE, and incomprehensible graphical representations of whatever that thing in the corner is. After five installments, you might expect to see some stagnation, but King’s Quest V is unlike anything previously seen in the series: you’ll visit a vast ocean and a dangerous castle; you’ll make friends by playing musical instruments; you’ll confront bandits, face off against a deadly snake, outwit a yeti, and OK it’s exactly the same as all the other games.

Actually, that’s not true—King’s Quest V lets you shove a cat into an empty sack of peas, so that’s different. What chiefly sets this installment apart from its predecessors is the introduction of 256-color graphics, full voice acting (at least in the CD-ROM version, which jarringly replaces virtually all written dialogue entirely), and a point-and-click interface, which helped set a standard for not only the series but the entire genre. Thankfully the puzzles didn’t set a standard for the genre as well, or else adventure gaming would’ve died off by the end of the ’90s.

What do you mean, “that actually happened”?

Thanks for playing, the entire adventure game industry. As usual, you’ve been a real pantload.

Thanks for playing, the entire adventure game industry. As usual, you’ve been a real pantload.

If you’re new to the series, or new to adventure games in general, King’s Quest V is the perfect place to start and then abruptly stop because nothing makes any sense. The story has some strong ties to previous entries in the series, particularly King’s Quest III, and the challenges are illogical even by adventure game standards. No, really, you tell me what to do with the block of moldy cheese, because I guarantee you’re wrong. Fables and folklore factor less into the game than in previous installments, so you’ll spend less time kissing frogs to turn them into princes and more time throwing pies at yetis.

Unless I’m forgetting about the fable where you die repeatedly of dehydration.

Unless I’m forgetting about the fable where you die repeatedly of dehydration.

The game centers around Graham, King of Crackers Daventry, and the opening cutscene plays out like a country song: A mysterious wizard (fine, maybe not like a country song) casts a spell that makes Castle Daventry and all of its inhabitants vanish. Graham returns from a walk to find that he’s lost his home, his family, and after a few minutes with Cedric the talking owl, his sanity. Speaking in a vaguely owlish falsetto that’s been the object of ridicule in the fan community for years, Cedric—who witnessed the whole thing without doing a thing to try to stop it—proceeds to tell Graham about this other wizard, Crispin, who can probably help Graham mount a rescue attempt. Cedric and Graham travel to Crispin’s house, and the kindly old wizard forces Graham to eat some leftover snake meat, gives him a useless old wand, and makes Cedric tag along so he can naysay everything Graham tries to do. Thanks, old guy! Now I’m super-prepared to rescue my family.

Oh, wait! I bought a pie. Now I’m super-prepared.

Oh, wait! I bought a pie. Now I’m super-prepared.

In true King’s Quest fashion, the bulk of the game is spent combing an expansive overworld map for items to filch and random puzzles to solve, which will somehow eventually lead you to the part of the game that has anything to do with the main plot. Unlike previous King’s Quest games, however, any sense of open-endedness is an illusion: you’ve got access to over 100 screens from the very beginning of the game, but there are only two or three of them at any given time with anything you can do. After completing one challenge, another one usually opens up somewhere else, either because of an item you now possess or due to an unrelated event that’s triggered without your knowledge. This dichotomy of boundless exploration and largely linear puzzle progression makes it tedious to find each puzzle, let alone discern whether you have the right tools to craft a solution.

Hey, this bear wasn’t here before! Only you can slow the growth of the bear population by not picking up a dead fish four screens to the east.

Hey, this bear wasn’t here before! Only you can slow the growth of the bear population by not picking up a dead fish four screens to the east.

I go into this in more specific detail elsewhere, but the short, spoiler-free version is that King’s Quest V consistently fails to provide clear objectives, clear feedback, and clear causality for its challenges. Backtracking through a dark forest leads to screens you’ve never seen before, so did the layout of the forest suddenly change, or did you discover a new path you didn’t notice before, or are you just hopelessly inept at navigation? You walk into an inn, and some grungy bandits tie you up and throw you into the cellar to die if they notice your presence—are you supposed to eavesdrop on them, beat them up, sneak around them, or give them clandestine back massages? You buy a pie—should you eat the pie??? Random guesswork and pure luck tend to play a bigger role in the puzzle-solving than logical deduction and creative thinking; the game simply does not supply the kind of guidance necessary to play this like an adventure game instead of a training program for wannabe psychics.

Be sure to take occasional breaks from glaring angrily at the screen, or else you’ll end up like these guys.

Be sure to take occasional breaks from glaring angrily at the screen, or else you’ll end up like these guys.

What kills me (literally and figuratively) is that Cedric the Cowardly and Thoroughly Useless Talking Owl should be a built-in hint system and occasional puzzle-solver. Instead, his contributions to Graham’s adventure include getting captured, warning Graham not to get bitten by the poisonous snake that’s currently biting him, directing Graham toward the bakehouse he just came from, warning Graham not to fall into the river as he’s falling into the river, telling Graham that baked goods are delicious, declining any request to do anything requiring physical effort, indicating the way back to the bakehouse, and PLEASE CAN WE GO TO THE BAKEHOUSE. Absurd puzzle solutions and boneheaded death sequences become even more irritating when you consider how much talent Cedric is wasting by “thinking big thoughts” all the time instead of telling you the boat has a leak before you ride it out to sea.

Hoo! Don’t go into the forest, Graham! There might be danger on this adventure!

Hoo! Don’t go into the forest, Graham! There might be danger on this adventure!

It’s a shame, too, because the rest of the game is reasonably solid. The point-and-click interface is clean and simple. The graphics are some of the prettiest I’ve seen in an adventure game—I do believe I emitted an “ooh” or an “aah” on numerous screens. A few puzzles have multiple solutions, which adds to the replay value. The story is interesting enough, the characters are fairly memorable, and the writing has a good amount of personality. All these are very positive things.

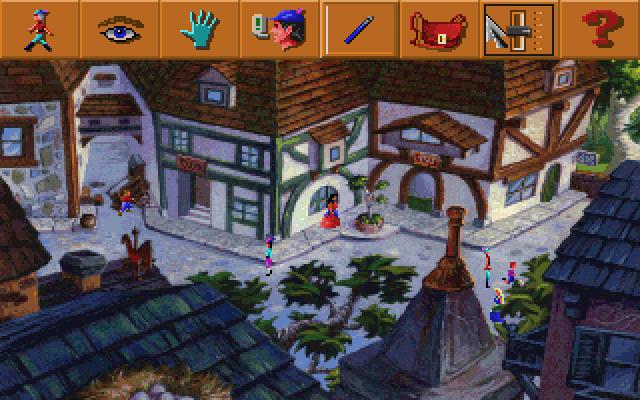

See? It doesn’t look like the kind of game you’d want to throw shoes and tomatoes at, right?

See? It doesn’t look like the kind of game you’d want to throw shoes and tomatoes at, right?

The voice acting ranges from obnoxious to pretty decent; audio quality isn’t terrific, and you can tell the cast is comprised mostly of Sierra programmers who walked into work one morning and found a script sitting on their desks, but there’s a level of enthusiasm that makes it seem like everyone is truly trying their best. The sound effects are serviceable—nothing stands out as particularly amazing or awful. The same goes for the music…with the exception of a few themes that do not go well with standard MIDI instruments—an overreliance on high-pitched honking and bleating accordions makes the town theme, for one, almost unbearable.

Honka HONK HONK honka HONK HONK honka SOUND OFF…

Honka HONK HONK honka HONK HONK honka SOUND OFF…

As a sequel, King’s Quest V is perfectly acceptable—the game retains the core feel of the series while attempting to improve the surface aspects, often bringing in elements from past games for the sake of having run out of other ideas continuity and nostalgia. I’d say that the puzzles are a little more obtuse than usual, but then again we’re talking about the series that makes you spell “Rumpelstiltskin” by reversing the alphabet per the suggestion of a vague note on the other side of the world. As an adventure game, independent of the series, King’s Quest V is best played by someone else who knows what they’re doing while you watch. The gameplay ruins the game, but it’s not even that the puzzles themselves are bad—it’s the misleading or altogether absent communication about what is actually a puzzle, what does and doesn’t work, and why things happen that makes the game so exasperating.

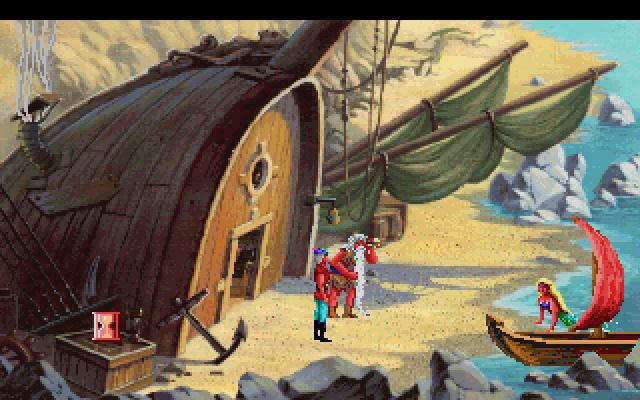

Let’s pretend this screenshot is somehow related to what I’m saying.

Let’s pretend this screenshot is somehow related to what I’m saying.

If you’re a fan of the series or are doing a term paper on questionable game design, King’s Quest V is worth a look. If you’re just looking for another adventure game to play, I’d sooner have you try Space Quest 0, Gemini Rue, or any other game I can shamelessly plug to trick you into reading more of my articles. At the very least, keep a good walkthrough handy—and don’t be surprised if you look up the solution to one puzzle and discover there are three others you had no idea existed that you have to solve first.