While videogames keep evolving and growing up as media, their sequels have finally caught up with other types of mainstream media—in later generations, many of us have started saying stuff that used to be reserved to the movie realm, like “sequels are never as good as the original” or that “maybe they shouldn’t have bothered doing a sequel at all”.

Of course, sequels are still technologically superior to their predecessors, but with every new coat of polished graphics or gameplay these games usually suffer from a lack of depth or the personality that made them unique when their new IP was first introduced.

Every year, we are hyped to play the sequels of those games that made a great first (second, third…) impression on us, and sometimes we end up with a stale, short, and/or watered down product compared to the original.

But times weren’t always like this. Back during the 8 and 16-bit eras, sequels had a good long run being increasingly better than their originals; long gone are the days when we got excited whenever we got our hands on a refined sequel of a game we could not believe could be improved—like Contra, Super Mario Bros., or Castlevania—and it actually paid off.

Actually, sequels were even more outstanding during the early days of videogames. Heck, some of them actually were complete new games. On this article, we’ll remember a few titles from a time when developers would experiment and take risks with the IP they had in their hands, instead of simply slapping a number “2” on the game’s title and be done with it.

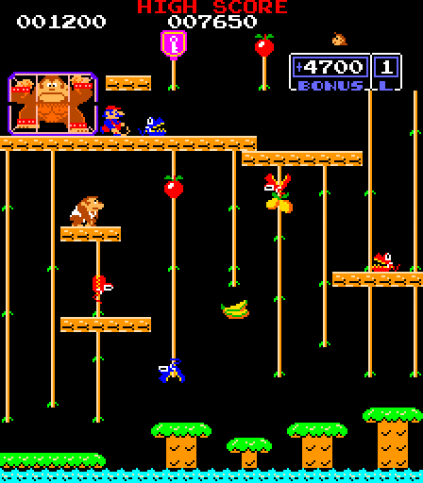

Donkey Kong Jr. (1982) is the sequel of the first popular game designed by (Super Mario and Legend of Zelda creator) Shigeru Miyamoto. While it’s named only slightly different than the original, Donkey Kong Jr. is entirely a new game. It posses completely new gameplay and a new character to play with and—shockingly—it’s the first and only time Mario has ever played the role of a game’s villain.

You know what they say: You either die a hero, or live long enough to become the villain—and it still applies if you have extra lives.

You know what they say: You either die a hero, or live long enough to become the villain—and it still applies if you have extra lives.

Excuse me if I go way back to the days of the Atari 2600, but Cosmic Ark (1982) is the first game I have memory of playing when I was a kid, as well as being believed to be the first videogame sequel released on a game console. It is said that the spaceship you defend in this game is the same one that escapes at the end of the game Atlantis, a totally different title released earlier that year. While the link between these two is subtle, this was one of videogaming’s first attempts to tell us a story. Also, at the end of Cosmic Ark (that is, when you are no longer able to withstand the increasing difficulty of the game), there’s also another small spaceship escaping from the Ark’s explosion, forecasting the announcement of a sequel never made.

The first game had you shooting invaders from space, now you’re playing Space Noah…

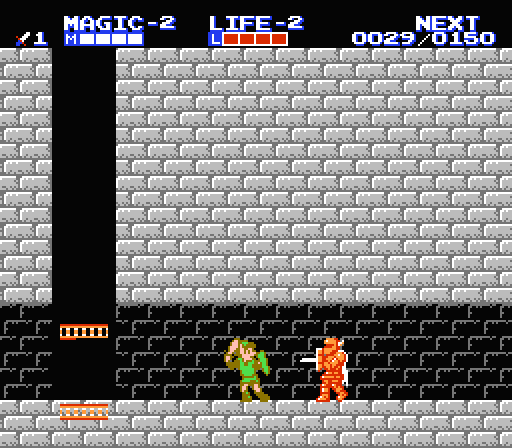

Zelda II: The Adventure of Link (1988) is another fine example of the bold attitude from that era: Instead of revamping whatever elements from the previous game, Zelda II was created from scratch and made into an entirely new title. The game is the only side-scroller of the series—it’s gameplay is also more action-oriented gameplay—and it includes RPG elements (like experience, levels, and magic) in its formula. Although, this sudden difference backfired quite a bit since many followers have considered Zelda II the black sheep of the series because of how different this game is compared to the original. Something about the lack of items, puzzles, and…I’ll leave the rest of the complaints to someone else; I actually love this game.

It was basically pixelated Dark Souls to me!

It was basically pixelated Dark Souls to me!

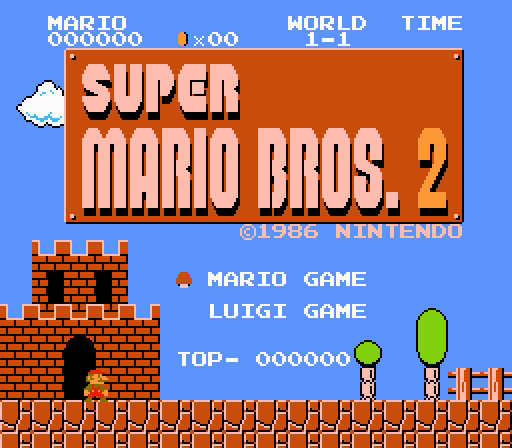

Talking about black sheep, let’s talk about Super Mario Bros. 2. One day, Super Mario series creator Shigeru Miyamoto got super bored, and wondered what could be done for its next installment to make it less lame, and make it radically different. The changes he envisioned that night would change the face of gaming for decades to come.

Of course I’m kidding—We all know that Super Mario Bros. 2 is the American localization of a Japanese game titled Doki Doki Panic, so it’d be hard for anyone to trick you into thinking that the major differences in this game were actually deliberate. But the thing I’d like you all to remember is that this game was sent to America because the real Super Mario Bros. 2 released in Japan was merely an update from the original, that offered practically nothing new to the series (except for an almost unplayable difficulty level and the infamous poisonous mushroom). Japan denied exporting this game for doing what is now the industry’s standard.

That was literally slapping a number “2” on the game title and call it a day.

That was literally slapping a number “2” on the game title and call it a day.

On the other hand, there’s Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest. I wouldn’t be able to defend this game with the same enthusiasm as the last two, since I was also a victim of its frustrating and infuriating gameplay but still, I’d like to acknowledge the things the game tried to pull off on its very first sequel. It took the first steps for the series into an exploration-oriented adventure (it’s a long shot, but it was its first steps into what we consider the Metroidvania genre), and the game incorporated a day and night mechanic that we wouldn’t see again until The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. Personally, being caught at night in this game remains one of the most iconic moments from the 8-bit era.

Now this is what I call the Symphony of the Night!

As weird and unorthodox as some of the first videogame sequels were during the old days, I remember those as the remnants of a time when developers dared to do something new, or wanted their games to be something different. Those were the times when the industry pushed forward innovation and experimentation, as opposed to these days when publishers mostly invest in safe and already-tried formulas.

Of course there are some good videogame sequels out there that are worth your time, but it’s even hard to find out which follow-ups are actually great, because we tend to be condescending to some of them because “they present the same thing you loved from the last one, plus a little more”.

We shouldn’t patronize “a little more”—we should be demanding a lot from games that keep basically repackaging themselves year after year, ask for a full price at retail, and then bombard us with their vile downloadable content, loot boxes, or whatever other method publishers utilize to get their hands into our wallets.

Finally, let’s not forget that videogames are no longer just about graphics and gameplay; narrative has become a major ingredient in great games, and nothing kills it faster than a bucket-load of sequels.

Pretty much like Michael Connelly once mentioned about writing too many books about the same character: “It is like peeling the skin of an onion, with every book the onion keeps getting smaller.”